When people think of animated films, a few studios typically come to mind: Disney, Pixar, DreamWorks — giants of Western media with global reach. But there’s another name that commands just as much reverence among artists, filmmakers, and audiences alike: Studio Ghibli. Founded in 1985 by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and producer Toshio Suzuki, this Japanese studio has produced some of the most visually stunning, emotionally resonant, and narratively rich animated films ever made.

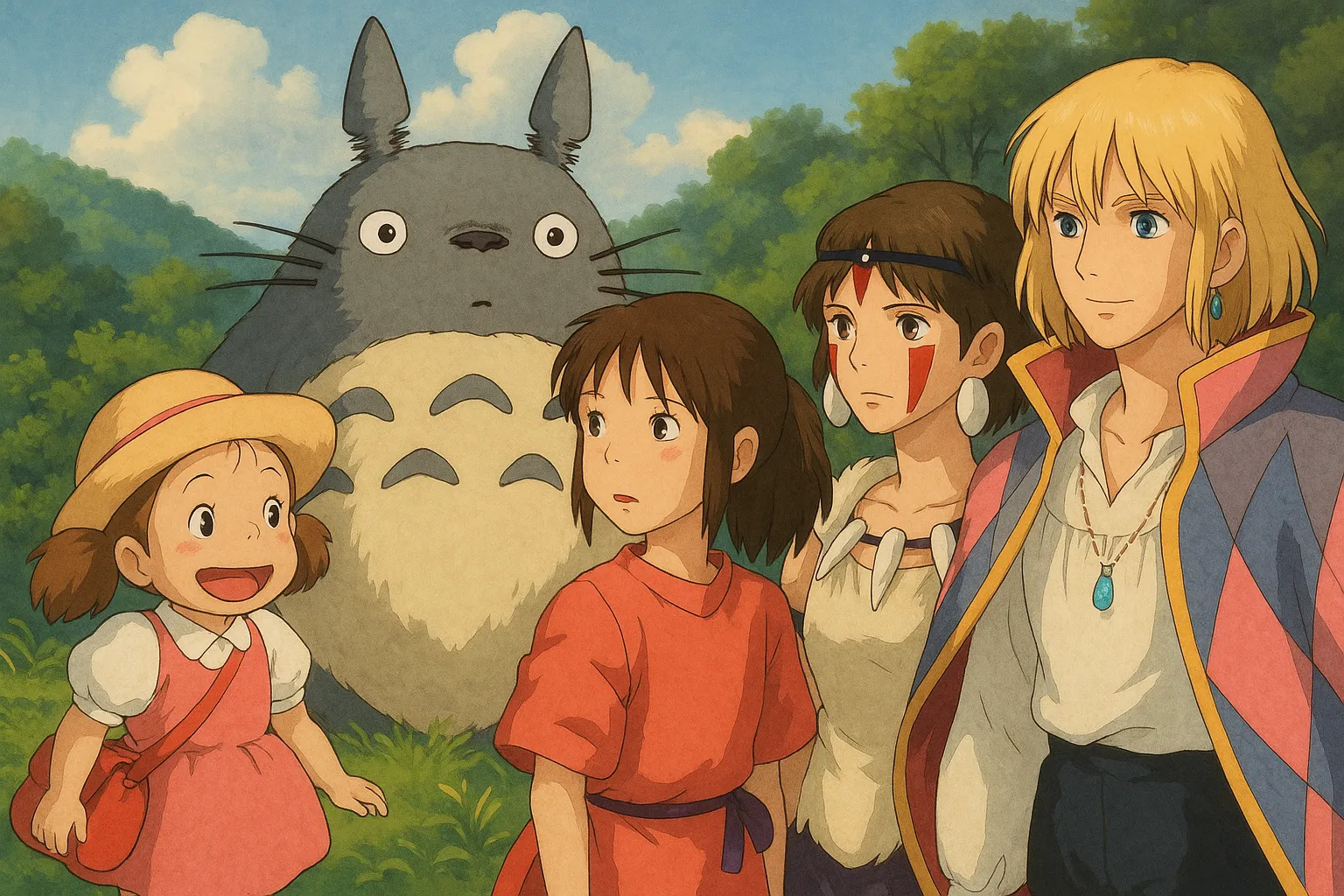

Titles like My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, and Howl’s Moving Castle have captivated audiences around the world — not only because of their whimsical visuals and lovable characters but because of their philosophical depth, environmental themes, and nuanced portrayals of human emotion.

But Studio Ghibli hasn’t just won the hearts of anime fans — it has left a profound and measurable impact on Western animation, influencing everything from film direction to character design, storytelling, and studio philosophy.

This blog will explore how Studio Ghibli reshaped the Western animation landscape, beginning with its origins and growing influence in the 1990s and early 2000s — leading to the stylistic and narrative shifts we see in animation today.

The Rise of Studio Ghibli: A Different Kind of Magic

Studio Ghibli’s approach to animation was always countercultural. While many Western animated films emphasized fast pacing, slapstick humor, and clear-cut good-versus-evil dynamics, Ghibli embraced quiet moments, moral ambiguity, and slice-of-life storytelling. Even its most fantastical films — like Spirited Away or Laputa: Castle in the Sky — are grounded in everyday emotions: fear, wonder, grief, longing, and growth.

Hayao Miyazaki, the studio’s creative heart, rejected the idea of “films for children” in the condescending sense. He once said:

“We don’t make movies for children. We make movies that children can watch — and adults can understand.”

This philosophy created stories that avoided typical tropes and allowed for multilayered interpretations. In films like Princess Mononoke, there are no absolute villains. Nature spirits and industrialists clash, but both are treated with empathy. In Spirited Away, the protagonist’s journey is not about defeating evil, but about maturing emotionally and rediscovering identity.

This tone — gentle yet complex — stood out in stark contrast to Western animation of the time, which was still recovering from the loud, zany energy of the 1980s and early ’90s. Ghibli’s storytelling offered a blueprint for slower, more thoughtful animation that didn’t talk down to its audience.

Spirited Away and the Western Awakening

While Ghibli films had been circulating in niche circles since the late 1980s, the breakthrough moment in the West came in 2002, when Spirited Away won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. It was the first (and still only) hand-drawn, non-English-language animated film to win the Oscar — and it stunned audiences unfamiliar with Japanese animation.

Spirited Away was distributed in the U.S. by Disney under a landmark deal brokered by Pixar’s John Lasseter, a longtime admirer of Miyazaki. Disney had previously licensed Ghibli films (Kiki’s Delivery Service, Princess Mononoke), but Spirited Away received a wide release and major marketing push.

This moment changed everything.

Critics lauded the film’s emotional depth, imaginative world-building, and strong female protagonist. Audiences — particularly those tired of formulaic children’s films — embraced its ambiguity and originality. American animators took notice. The film became a benchmark of artistic integrity, and a reference point for what animation could be when freed from the confines of commercial expectations.

The impact was immediate. Studios started to greenlight more artistically ambitious projects. Young Western animators began citing Ghibli films as formative influences. The belief that animation could be both aesthetic and literary became harder to ignore.

The Ghibli Influence on Pixar and Beyond

Perhaps the most direct influence Ghibli had in the West was on Pixar. Studio co-founder John Lasseter was vocal about his admiration for Miyazaki, calling him “the greatest animator living today.” Under his leadership, Pixar embraced storytelling values that closely mirrored Ghibli’s — emotional sincerity, character-driven narratives, and moral nuance.

Compare Spirited Away to Inside Out, or Kiki’s Delivery Service to Turning Red. While these are distinct films, the fingerprints of Ghibli’s influence are evident:

- Coming-of-age journeys where the stakes are emotional rather than physical

- Magical realism used as a backdrop for inner transformation

- Absence of clear villains in favor of internal or social conflict

- Strong female protagonists that feel authentic and human

- Attention to small moments — a character cooking breakfast or watching the wind blow through grass

But Pixar wasn’t the only studio taking notes.

DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon series, Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe, and even Disney’s Raya and the Last Dragon all exhibit Ghibli-esque traits. These include the rejection of binary morality, the embrace of environmental themes, and the willingness to slow down and let beauty and silence speak.

The Visual Legacy: A New Aesthetic Language

Ghibli’s impact on visual storytelling cannot be overstated. From character design to background art, the studio introduced a softer, more painterly aesthetic that contrasted with the bold lines and exaggerated expressions of Western cartoons.

Miyazaki and his team favored natural landscapes, tactile environments, and intricate details that grounded their worlds in reality — even when the narrative was fantastical. The food in Ghibli films became its own genre of art. The forests, skies, and water were rendered with near-reverence.

This style has influenced a wave of independent animators and art directors in the West. You can see it in the color palettes of Over the Garden Wall, the textured animation of Wolfwalkers, and the slice-of-life stillness in The Midnight Gospel.

Even Western video games like Ori and the Blind Forest and Ni no Kuni (which was developed with help from Studio Ghibli) reflect this visual legacy.

Ghibli proved that hand-drawn animation, far from being obsolete, had its own timeless magic — and Western creators listened.

A Different Philosophy: The Power of Ambiguity and Emotional Realism

One of Studio Ghibli’s most lasting influences on Western animation is its philosophy of storytelling. Unlike many traditional Western animated films that emphasize speed, clarity, and resolution, Ghibli embraces narrative ambiguity, emotional subtlety, and the quiet beauty of everyday life.

Hayao Miyazaki once said:

“We are not trying to entertain children. We are trying to show them life.”

This core belief shaped stories that resist easy classification. A film like My Neighbor Totoro has no villain, no dramatic climax, and no moral lesson spelled out at the end — and yet, it leaves a deep emotional impression. It presents the world as it is: mysterious, tender, and unpredictable.

In contrast, many Western animated films before the 2000s relied heavily on formula: a hero’s journey, a comic sidekick, a conflict resolved in a grand finale. Ghibli’s influence challenged this structure. By showing that stillness, uncertainty, and character introspection could drive an animated film, it invited Western creators to think differently.

Films like The Iron Giant, Coraline, Inside Out, and The Red Turtle — all embrace this Ghibli-inspired space of emotional realism, where the audience is invited not to consume a lesson, but to feel and reflect.

Reimagining the Environment: Nature as Sacred, Not Background

Environmental themes are woven into the very fabric of Ghibli’s worldview. From the lush forests of Princess Mononoke to the rising waters of Ponyo, nature is never just a setting — it is a character, a spiritual force, and often, a source of conflict and wisdom.

In Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, humans live on the edge of an ever-expanding toxic jungle, and the protagonist, Nausicaä, doesn’t seek to destroy it — she seeks to understand and coexist with it. Similarly, in Princess Mononoke, the tension between nature and industry is portrayed with moral complexity. There is no “evil” villain; only clashing perspectives on survival, progress, and stewardship.

This eco-centric lens was relatively rare in Western animation at the time. While some Disney films like Bambi or The Lion King had nature-centric settings, Ghibli made environmental consciousness a central narrative theme, not a backdrop.

Western studios took notice. Films such as Wall-E, Avatar, Happy Feet, and Frozen II carry messages of climate change, ecological balance, and the consequences of human action on the planet — all informed, in part, by the kind of ecological storytelling Ghibli pioneered.

But Ghibli went further — it spiritualized nature. It reminded audiences that forests, rivers, and animals hold mystery, memory, and sacredness. This perspective now appears regularly in both Western children’s animation and fantasy works, reinforcing the idea that animation can be a tool for teaching environmental empathy.

Empowered Girls and Gentle Boys: Rewriting Gender Norms

Another defining feature of Ghibli’s legacy is its treatment of gender. At a time when many Western animated films revolved around male heroes and damsels in distress (or princesses awaiting transformation), Studio Ghibli offered something radically different: proactive, courageous, and emotionally complex female protagonists.

From Nausicaä and Kiki to Chihiro and Sophie, Ghibli girls are never defined by romantic goals or physical beauty. They are defined by their agency, kindness, resilience, and internal growth. They don’t need saving — they’re often the ones doing the saving. And when love appears, it’s gentle, non-sexual, and supportive — a partnership, not a prize.

Western studios began to follow this model. Disney’s shift from Cinderella to Brave, Moana, and Frozen clearly reflects Ghibli’s impact. These newer films focus on self-discovery, family, community, and adventure — rather than romantic love.

But Ghibli also redefined masculinity. Characters like Haku (Spirited Away), Ashitaka (Princess Mononoke), and Seiji (Whisper of the Heart) are gentle, thoughtful, respectful, and emotionally open. They are strong without being aggressive. They are brave without being violent.

This dual approach — strong girls and gentle boys — offered a more inclusive vision of gender roles that deeply resonated with younger viewers and creatives, encouraging Western storytellers to embrace similar complexity in their characters.

The Emotional Blueprint: From External Stakes to Internal Transformation

What do Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Spirited Away have in common? None of them follow the standard Hollywood plot arc. There’s no villain to defeat, no final boss, no explosive ending. Instead, Ghibli stories revolve around internal transformation — characters growing emotionally, gaining new perspectives, or healing from grief.

This shift from external to internal stakes has significantly influenced Western animation, especially in shows and films targeted at older children, teens, and young adults.

Pixar’s Inside Out quite literally maps the inner world of a child’s emotional development. Wolfwalkers (Cartoon Saloon) follows a protagonist learning empathy for the people she once feared. Steven Universe is perhaps one of the most Ghibli-influenced series in tone, pacing, visual style, and emotional resolution — it focuses more on understanding and reconciliation than on violence or competition.

Even action-oriented series like Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra show their heroes wrestling with trauma, identity, guilt, and empathy — concepts rarely centered in Western animation prior to Ghibli’s rising influence.

This emotional depth is now expected in animation — not just tolerated. That change owes much to the quiet power of Ghibli’s character-driven storytelling.

A Cultural Bridge: Bringing Japanese Aesthetics into Western Homes

Studio Ghibli also played a major role in bridging Japanese and Western animation traditions. Before the 2000s, many Western audiences viewed anime as niche or even alien. But Ghibli’s films — with their universal themes, gorgeous hand-drawn art, and transcendent soundtracks — made Japanese storytelling accessible without compromise.

The studio didn’t “Westernize” its content to appeal to global markets. Instead, it invited Western viewers to appreciate Japanese sensibilities: quiet pauses in action, seasonal transitions, respect for elders, Shinto spirituality, and minimalist dialogue.

Through Ghibli, audiences began to appreciate anime on its own terms. This opened the door for other Japanese films and series to reach broader Western markets — paving the way for titles like Your Name, Weathering With You, Belle, and even more experimental works like In This Corner of the World.

The rise of streaming services furthered this exchange. Platforms like Netflix and HBO Max acquired global Ghibli rights, bringing the full catalogue to homes worldwide — including places where anime had never before had such visibility.

Legacy and the Next Generation

Studio Ghibli’s influence is not just a matter of technique or theme. It’s philosophical, cultural, and emotional. It challenges animators and audiences alike to ask:

- Can we slow down and enjoy the moment?

- Can we tell stories without clear villains?

- Can animation be for everyone — not just children?

- Can we respect nature, understand our feelings, and embrace ambiguity?

The next generation of creators has already answered with a resounding “yes.” Whether it’s the gentle spirit of Bluey, the melancholy beauty of The Owl House, or the emotional sincerity of Encanto, Western animation has been irrevocably changed by Studio Ghibli’s values.

And with Ghibli’s new works (like The Boy and the Heron) continuing to push boundaries, and new studios inspired by its ethos rising in the West, the legacy is far from over.

Final Thoughts: More Than a Studio, a Spirit

Studio Ghibli is more than just a production house. It’s a spirit — a way of telling stories that honors the small, values the quiet, and believes deeply in the emotional power of animation.

Its influence on Western animation has not only shaped how stories are told, but what kinds of stories are even possible. In doing so, Ghibli has given animators and audiences alike permission to dream, to feel, and to grow.

Because as Spirited Away reminds us, sometimes the most powerful journeys are the ones that bring us back to ourselves.